Inflation's Defining Role in the American Revolution

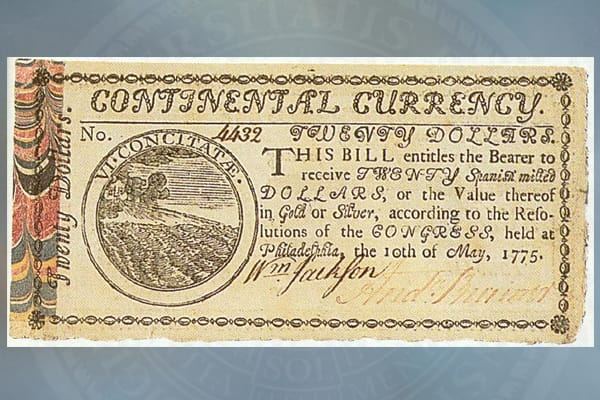

Inflation during the American Revolution was a significant economic issue that affected the war effort and daily life in the colonies. The primary causes of inflation included the excessive printing of currency, disruptions in trade, and wartime shortages. The Continental Congress issued paper money, known as Continental currency, to fund the war effort, but the overproduction of this currency led to severe depreciation and rampant inflation.

Causes of Inflation

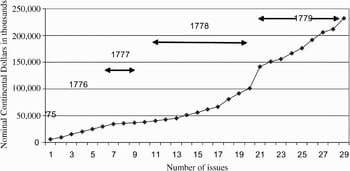

- Excessive Printing of Currency: The Continental Congress lacked the power to levy taxes and relied heavily on printing money to finance the war. Between 1775 and 1780, Congress issued approximately $241 million in Continental currency. However, without sufficient backing in gold or silver, this currency rapidly lost its value. By 1781, the Continental currency had depreciated to the point where it was worth just 1/40th of its face value.

- Trade Disruptions: The British naval blockade severely restricted American trade, leading to shortages of essential goods. This scarcity drove prices up, contributing to inflation. Imports of goods like tea, sugar, and textiles became scarce, and their prices soared as a result.

- Wartime Shortages: The demands of the war effort led to shortages of goods and materials. For example, military requisitioning of food, supplies, and livestock for the Continental Army reduced the availability of these items for civilian use. The increased demand for these limited resources further drove up prices.

Events Resulting from Inflation

- Economic Hardship: Inflation eroded the purchasing power of ordinary citizens, leading to widespread economic hardship. People found it increasingly difficult to afford basic necessities. This economic strain was particularly acute for soldiers and their families, who often relied on Continental currency for their pay.

- Civil Unrest: The severe inflation and resultant economic distress led to instances of civil unrest. In 1779, food riots broke out in several cities, including Philadelphia and Boston. Citizens, frustrated by the high cost of living and food shortages, protested against merchants accused of hoarding and price gouging.

- Undermining the War Effort: Inflation weakened the American war effort by eroding the value of soldiers' pay and making it difficult to procure supplies. Soldiers often faced delays in receiving their wages, and when they were paid, the currency was nearly worthless. This demoralized the troops and made it harder to maintain an effective fighting force.

Measures Taken to Address Inflation

- Price Controls and Rationing: To combat inflation, some states implemented price controls and rationing. For example, in 1777, Massachusetts set maximum prices for various goods and services. However, these measures were often difficult to enforce and sometimes led to black market activity.

- Loans and Foreign Aid: The Continental Congress sought loans and financial aid from foreign allies, particularly France. French loans and subsidies played a crucial role in stabilizing the American economy and supporting the war effort. In 1781, the French provided a substantial loan that helped fund the crucial Yorktown campaign.

- Issuance of New Currency: In an attempt to stabilize the currency, Congress issued new forms of money. In 1780, they introduced a new series of Continental bills backed by future tax revenues. However, confidence in paper currency was so low that these new bills also struggled to maintain value.

- Taxation and Reforms: Recognizing the limitations of printing money, Congress began to advocate for taxation to support the war effort. In 1781, Robert Morris was appointed Superintendent of Finance. He implemented significant financial reforms, including the establishment of the Bank of North America, which helped restore some confidence in American finances by providing a more stable currency and facilitating government transactions.

Food Riots

The experience with inflation during the Revolution also fostered a distrust of paper money that persisted in American political culture for decades. This skepticism influenced subsequent monetary policies and debates about the role of government in regulating the economy.

The food riots during the American Revolution were significant events that underscored the economic and social strains faced by the colonies amidst the war. Root causes of these riots included severe inflation, wartime shortages, and speculative practices by merchants. The rampant inflation, driven by the overproduction of Continental currency, eroded the purchasing power of the populace, leading to widespread economic hardship and civil unrest.

Root Causes of the Food Riots

- Inflation: One of the primary causes of the food riots was inflation. The Continental Congress's decision to print large amounts of paper money to finance the war effort led to the devaluation of the currency. By 1779, the value of Continental currency had plummeted, with goods costing significantly more than their pre-war prices. For example, flour prices in Philadelphia increased from £3 per barrel in 1777 to £100 per barrel in 1779.

- Wartime Shortages: The British naval blockade and the war's disruption of agricultural production led to severe shortages of essential goods. Farmers were reluctant to bring their produce to market, fearing requisitioning by the military or price controls that would force them to sell at a loss. This scarcity further drove up prices, exacerbating the economic strain on ordinary citizens.

- Speculation and Hoarding: Merchants and speculators often hoarded goods to sell at higher prices, taking advantage of the inflationary environment. This practice worsened shortages and fueled public anger against perceived profiteers.

The Food Riots: Locations, Events, and Leadership

- Boston, 1777: One of the earliest and most significant food riots occurred in Boston in 1777. Women, many of whom were soldiers' wives, led the charge against merchants they accused of hoarding and price gouging. Armed with weapons and determination, they marched to stores and warehouses, seizing goods and selling them at what they considered fair prices. This action was not merely spontaneous but organized, reflecting deep-seated frustration with the economic conditions.

- Philadelphia, 1779: In Philadelphia, the food riots of 1779 were driven by skyrocketing prices and food shortages. Women played a central role in these protests as well, demonstrating against merchants and demanding fair pricing. On January 25, 1779, a group of women confronted merchants and compelled them to sell their goods at prices the women deemed reasonable. The riots in Philadelphia also saw the involvement of the "Mechanics' Committee," a group representing artisans and laborers, which supported the women's actions and called for broader economic reforms.

- Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1779: Another notable riot took place in Lancaster in 1779. Here, the local populace, frustrated by high prices and food scarcity, targeted merchants suspected of hoarding grain. The rioters seized stored grain and redistributed it at lower prices. This action was part of a broader movement across Pennsylvania, where citizens took direct action to address economic injustices.

Consequences and Impact

The food riots had several significant consequences:

- Government Response: The riots forced local and state governments to take action. In some cases, authorities implemented temporary price controls and anti-hoarding laws to stabilize the situation. For example, in Pennsylvania, the state government enacted measures to curb speculation and ensure fair distribution of goods.

- Social Unrest: The riots highlighted the deep social and economic divides within the colonies. The involvement of women and laborers in these protests underscored the widespread impact of inflation and shortages on ordinary citizens. The unrest also reflected broader frustrations with the Continental Congress and local authorities' inability to address economic grievances effectively.

- Economic Policy: The food riots influenced economic policy during and after the war. The experiences of inflation and scarcity prompted calls for a more stable and regulated economic system. These events contributed to the eventual framing of the U.S. Constitution, which granted the federal government greater powers to regulate commerce and currency.

The Role of Inflation in Outbreaks of Violence

Inflation played a central role in leading to the outbreaks of violence seen in the food riots. As prices for basic necessities skyrocketed, the purchasing power of the Continental currency diminished, leaving many unable to afford food and other essentials. This economic strain created a fertile ground for social unrest. The public's frustration was often directed at merchants and speculators, whom they blamed for exacerbating shortages and driving up prices through hoarding and profiteering.

Inflation during the American Revolution was a significant and destabilizing economic force. Driven by the necessity to finance the war effort without the power to levy taxes, the Continental Congress resorted to printing paper money, which resulted in rampant inflation. This article delves into the statistical details of inflation during the American Revolution, compares it to other revolutions, and explores its implications on subsequent U.S. monetary and fiscal policies.

American Revolution Inflation by the Numbers

The Continental Congress began issuing paper money, known as Continental currency, in 1775. By 1780, approximately $241 million in Continental currency had been issued. The overproduction of this currency, combined with a lack of backing by gold or silver, led to rapid depreciation.

- Depreciation Rates: By the end of 1776, the Continental dollar had already lost about 20% of its value. By 1778, the value of the Continental dollar had declined by 75%. By 1781, the depreciation had become so severe that it took 100 Continental dollars to equal one silver dollar, effectively rendering the currency nearly worthless.

- Price Increases: Prices for goods skyrocketed as the value of the Continental currency plummeted. For example, in 1777, a bushel of corn cost about $1 in Continental currency; by 1780, the price had soared to $80. A similar trend was observed for other essential goods. The price of flour rose from $5 per hundredweight in 1777 to $46 by 1779.

- Inflation Rate: During the height of the war, the annual inflation rate was estimated to be around 20-25% per month. This hyperinflation eroded the purchasing power of the currency and created significant economic instability.

Comparison to Other Revolutions

When comparing inflation during the American Revolution to other revolutions, such as the French Revolution (1789-1799) and the Russian Revolution (1917), some stark differences and similarities emerge.

- French Revolution: The French Revolution saw significant inflation, particularly with the introduction of the assignat, a paper currency backed by confiscated church properties. Initially, the assignat helped stabilize the economy, but excessive printing led to hyperinflation. By 1795, the assignat had lost 99% of its value, similar to the depreciation experienced with the Continental currency.

- Russian Revolution: The Russian Revolution also experienced severe inflation. The collapse of the Tsarist regime and the ensuing civil war led to economic chaos. Between 1917 and 1922, the Russian ruble depreciated by over 1,000 times. The hyperinflation during the Russian Revolution was comparable in scale to the American and French revolutions.

Implications for U.S. Monetary and Fiscal Policy

The experience of inflation during the American Revolution had profound implications for U.S. monetary and fiscal policy.

- Constitutional Reforms: The Articles of Confederation had left the federal government with limited powers to regulate commerce and currency. The hyperinflation experienced during the Revolution highlighted the need for a stronger central government with the authority to manage economic policy. The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, granted Congress the power to coin money, regulate its value, and levy taxes, addressing the weaknesses that had led to rampant inflation.

- Creation of the U.S. Mint: In 1792, Congress established the U.S. Mint and authorized the production of coins. This move aimed to create a stable and reliable currency backed by gold and silver, restoring confidence in the nation's money.

- Fiscal Responsibility: The Revolutionary War experience underscored the importance of fiscal responsibility. Alexander Hamilton, as the first Secretary of the Treasury, implemented policies to stabilize the national economy. His initiatives included the federal assumption of state debts, the creation of a national bank, and the establishment of a tax system to provide a steady revenue stream for the government.

- Bank of North America: Established in 1781, the Bank of North America was an early attempt to stabilize the economy by providing a stable currency and facilitating government borrowing. This institution laid the groundwork for future central banking efforts in the United States.

- Long-term Economic Policies: The hyperinflation experience influenced the nation's long-term approach to economic policy. The U.S. government became cautious about excessive money printing and emphasized the need for a balanced approach to fiscal and monetary policy to avoid similar economic instability in the future.

Inflation during the American Revolution was a defining economic challenge, driven by the overproduction of Continental currency and exacerbated by wartime disruptions. The depreciation of the Continental dollar, skyrocketing prices, and rampant inflation created significant economic hardship. Comparing this experience to other revolutions reveals common themes of hyperinflation driven by excessive currency issuance. The lessons learned from this period had lasting implications on U.S. monetary and fiscal policy, leading to constitutional reforms, the establishment of a stable currency system, and a focus on fiscal responsibility. The American Revolution's inflationary experience thus played a crucial role in shaping the economic foundations of the United States.